Venus

Throughout art history and archaeology, the woman's naked body has continuously been objectified.This is even seen in these disciplines interpretations of sculptures dating back to prehistoric times - before the concept of Venus, the Roman goddess of love and desire, even existed, and in places with no connection to Roman culture. Why is this? Why is it that men in the early days of archeological discovery could not possibly imagine that ancient representations of a woman's body could have any other purpose than to serve their desire and gaze at?

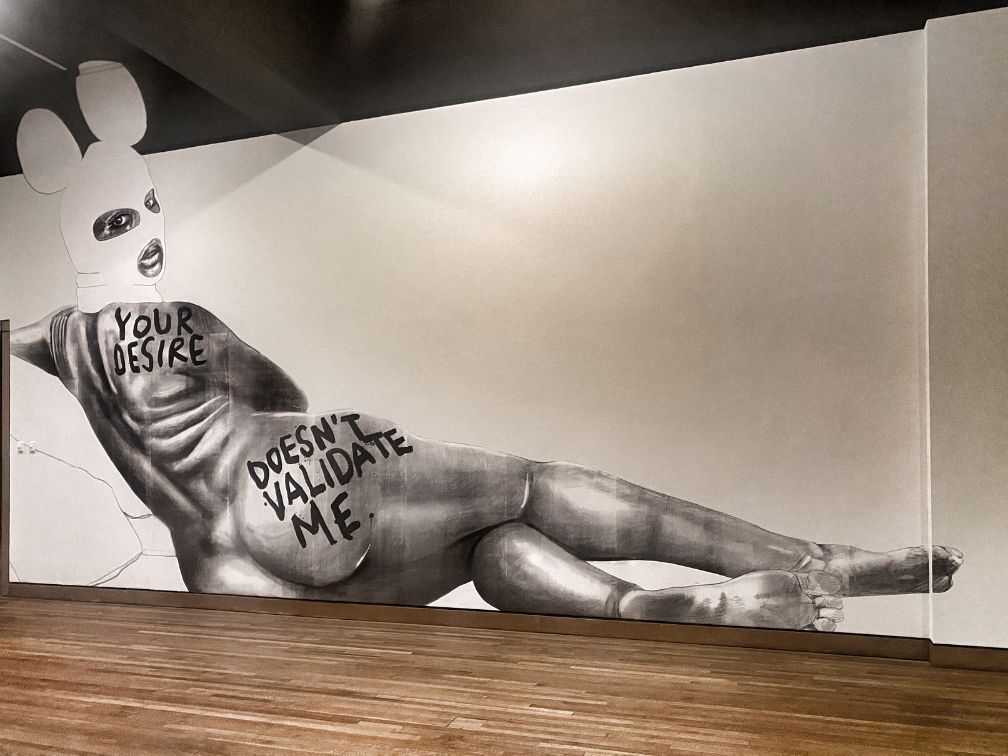

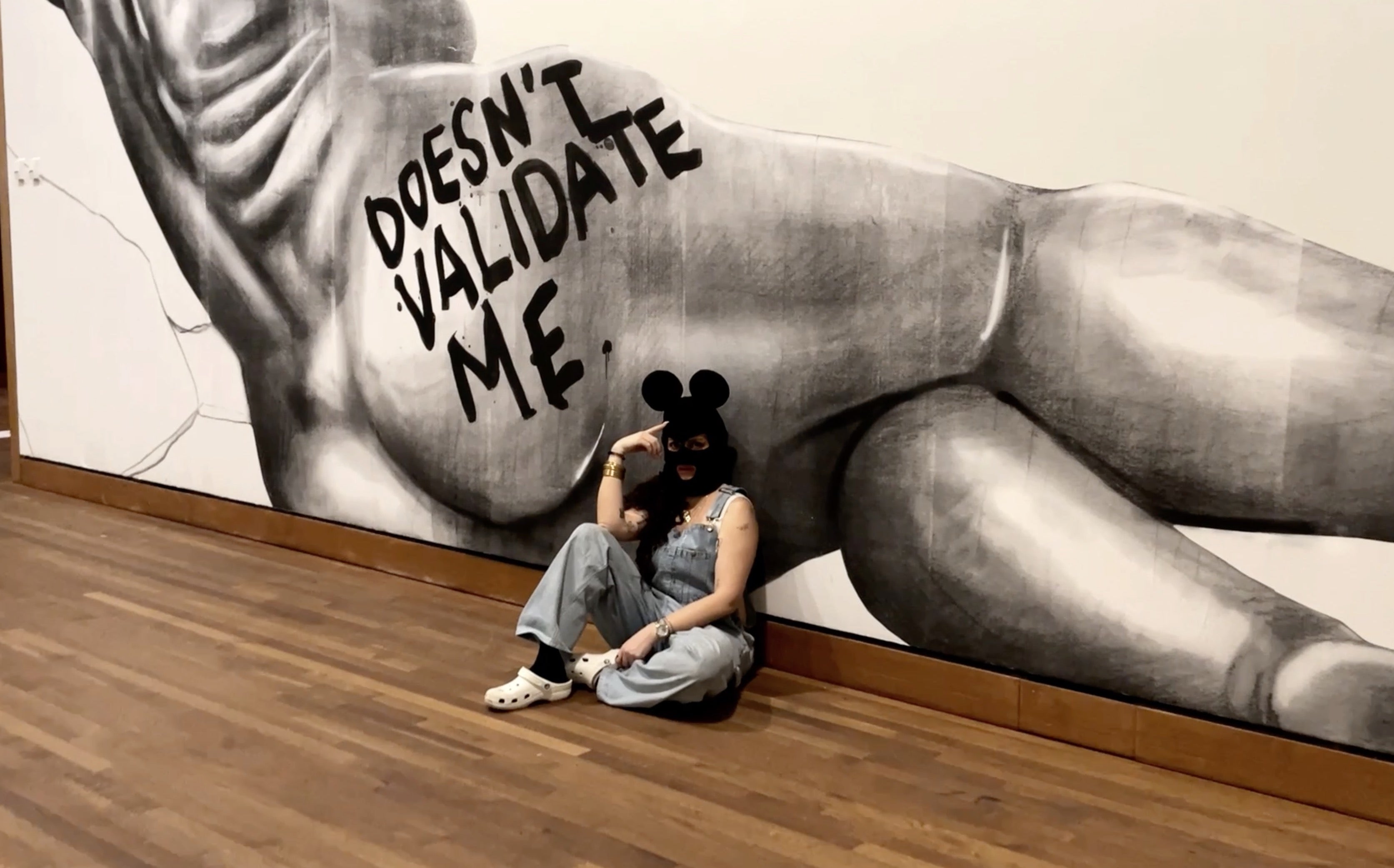

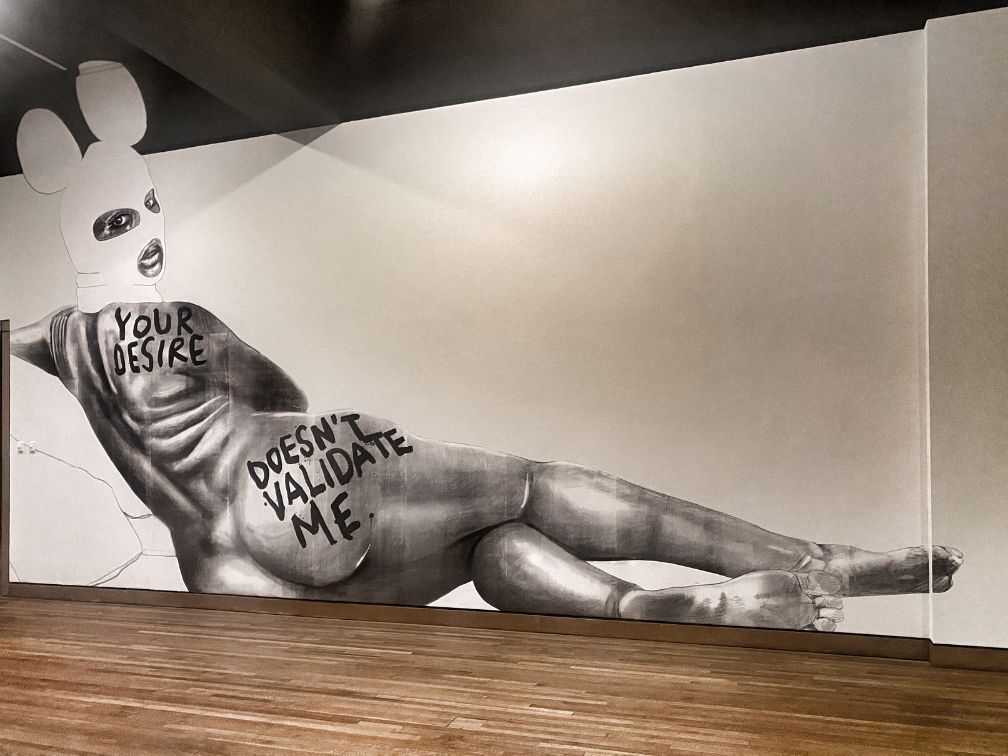

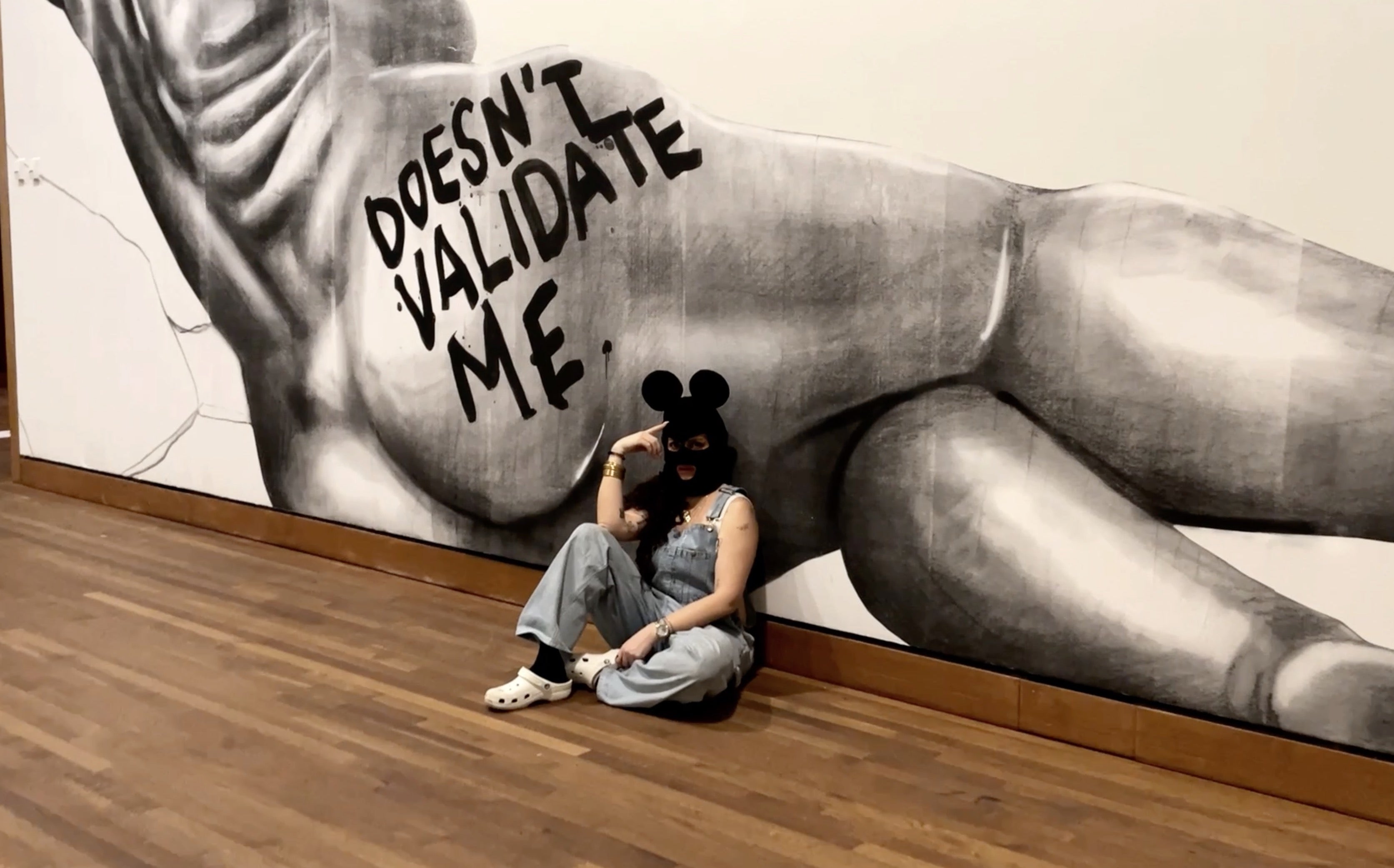

This is my take on Venus at her Mirror by Diego Velázquez. Again, why? Because in 1914, it was specifically attacked by Canadian suffragette Mary Richardson in order to raise awareness about women's rights:"I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government destroying Mrs. Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history. Justice is an element of beauty as much as colour and outline on canvas." Richardson's view was that, if people were outraged about her attack on the painting which was a mere representation of physical beauty, they should be equally if not more outraged over the government's torture of real women in British jails. With this act, she forced people to question the superiority of physical beauty over true beauty. One of morality and justice.Another art term uses to describe a painted naked female figure looking into a mirror is "vanity." The use of this word morally condemns the object of the painting. A subject chosen and painted by a straight man. For other straight men. Yet the only one who is morally condemned is the subject. The same subject might not have been asked to be painted much less stared at.

My take on Velázquez's Venus is one that is aware, one that chooses to be portrayed and one that stares back at the onlooker. One that has moved fully from object to subject.

Venus

Throughout art history and archaeology, the woman's naked body has continuously been objectified.This is even seen in these disciplines interpretations of sculptures dating back to prehistoric times - before the concept of Venus, the Roman goddess of love and desire, even existed, and in places with no connection to Roman culture. Why is this? Why is it that men in the early days of archeological discovery could not possibly imagine that ancient representations of a woman's body could have any other purpose than to serve their desire and gaze at?

This is my take on Venus at her Mirror by Diego Velázquez. Again, why? Because in 1914, it was specifically attacked by Canadian suffragette Mary Richardson in order to raise awareness about women's rights:"I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government destroying Mrs. Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history. Justice is an element of beauty as much as colour and outline on canvas." Richardson's view was that, if people were outraged about her attack on the painting which was a mere representation of physical beauty, they should be equally if not more outraged over the government's torture of real women in British jails. With this act, she forced people to question the superiority of physical beauty over true beauty. One of morality and justice.Another art term uses to describe a painted naked female figure looking into a mirror is "vanity." The use of this word morally condemns the object of the painting. A subject chosen and painted by a straight man. For other straight men. Yet the only one who is morally condemned is the subject. The same subject might not have been asked to be painted much less stared at.

My take on Velázquez's Venus is one that is aware, one that chooses to be portrayed and one that stares back at the onlooker. One that has moved fully from object to subject.